TQ and QT – pretty much the same thing? Not really!

The rules of English word formation indicate that TQ is about Quality per se, and QT describes a property of Translation, in most cases, of a particular translation. But of course, there’s lots more to it than that. In common parlance, QT generally refers to high quality translation, which implies that not all translations meet the same standards. In the past, high quality translation has been defined in terms of:

close correspondence of target language content with source language content (sometimes referred to as accuracy), and

compliance with target language conventions, terminology, style, and register, among other factors (sometimes broadly grouped together under fluency).

Translation that meets high quality standards conveys the core ideas expressed in source language content and reads as if it were written by a well-informed speaker of the target language, with the caveat that this process is almost never truly perfect. In this understanding, Quality Translation is treated as a generic property of translations and is not intended to be treated as a count noun or to refer to any one translation or translations.

The Multilingual Quality Metric (MQM)

MQM provides a detailed metric designed to evaluate translation content, to annotate errors with respect to assigned numerical values, and to calculate final scores that mirror the familiar 100-point scale common to most grading systems. MQM measures the use of words and the expression of ideas to produce numerical values that can be used to compare and analyze translation performance based on potentially varying user needs and client specifications. At all points in this discussion, the MQM quality measure is based on client requirements and specifications, which means that a high quality level for one project may not equate to a high level for another situation. By the same token, the quality produced by any given modality is subject to the rigor applied in preparing a given MT environment or the experience and skill of human translators, editors, and revisors.

Translation Quality in the context of any given project reflects a relative spectrum of quality used to measure translated content from its worst manifestations to the kind of high quality described as QT. It represents an attempt to measure target content in order to determine the extent to which it achieves the sometimes elusive goal of qualifying as Quality Translation. Thus TQ reflects a spectrum that generally is seen as culminating in QT, but QT itself varies depending on specifications..

This means that Quality Translation as a targeted value does not always reflect the transcendent quality described above. In the MQM context, it can also be defined as: translation that is accurate and linguistically correct for its audience and purpose, and that complies with all other specifications negotiated between the requester and provider, taking end-user needs into account. This definition implies then that Quality Translation reflects the quality level that is fit for purpose as defined by a given set of client requirements and specifications, which may be more or less demanding, depending on perceived user needs.

Typical use cases

We can consider the needs and purposes of translation projects, as exemplified by the following list. Note: the use cases cited here do not reflect any specific relationship to the “transcendent QT” cited above.

Websites and resources based on vast arrays of heritage data are being made available from existing multilingual archives;

A company that is uncertain about the market profitability of a new venture across localized markets experiments with inexpensive MT in order to reap signals about potential opportunities for market expansion;

Government entities and enterprises produce massive amounts of content that must be made available rapidly in a large number of languages;

Customer-relations websites that are critical to building brand loyalty;

Advertising and public relations texts that are highly brand-sensitive;

Machine descriptions and operating instructions that are safety-sensitive;

Translation students being taught best practices and methods who are being trained to achieve high Quality Translation.

Depending on the availability of human and budgetary resources and the quality of available machine translation (MT) options, clients with use cases 4-6 in this list are probably more likely to choose well-supported human translation (HT) or full post-edited machine translation (PEMT), and 7) has as its goal the familiarization of students with the principles of high Quality Translation, usually in the context of well-structured augmented translation.

Use case 1 in the list may be entirely too expensive for HT or the significant human expense for full PEMT if there is limited client demand, for instance, for significant fluency, so unedited machine translation (UEMT) is often the choice, with individuals perhaps exercising the option to request more stringent translation modalities depending on the criticality of safety, brand protection, and close linkage between translation product and overall end user satisfaction. Use cases 2 and 3 may well opt to use quality MT, with sampling, but maybe not full PEMT. Nevertheless, as the quality of MT improves, the absolute quality of translations produced in response to different requirements levels will vary depending on the amount of time and effort that should be invested in setting up the MT system used.

ASTM F 2575:2023 provides guidance on how to match production methods to use cases. It should again be noted that these levels reflect translation modalities and are not necessarily bound to translation quality.

ASTM F 2575:2023, Annex A

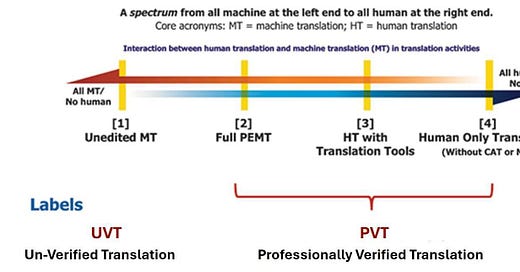

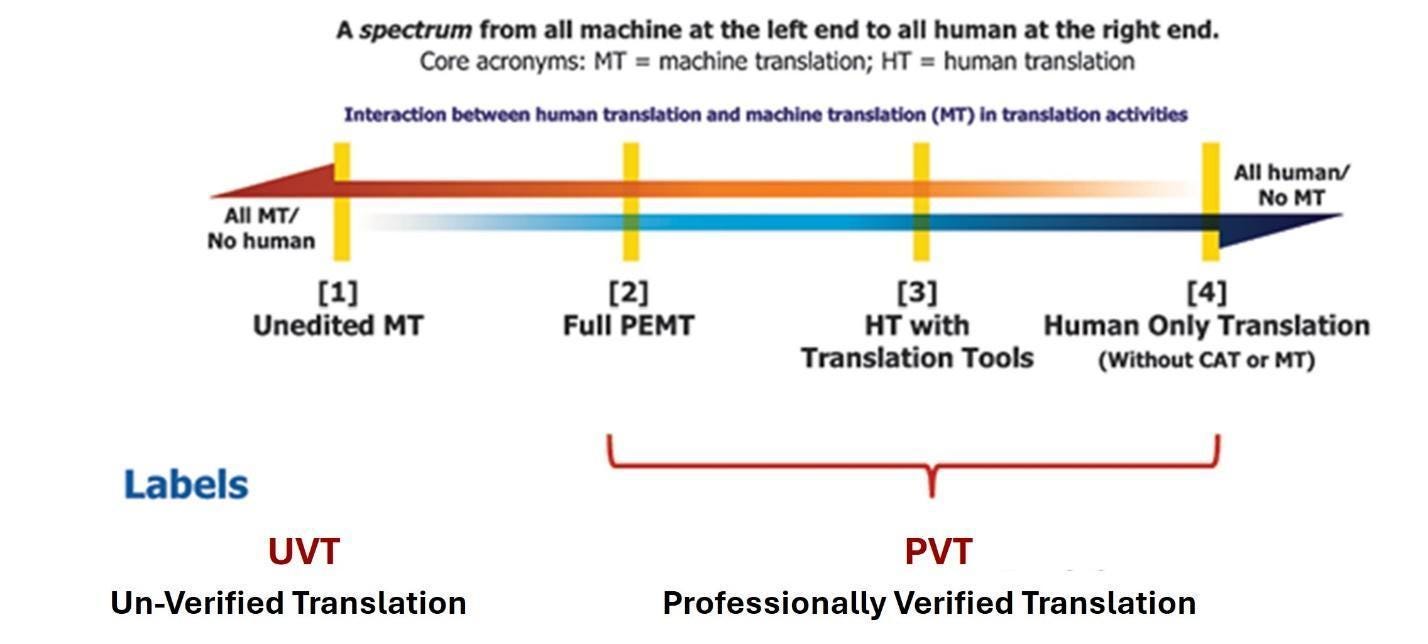

Figure 1: Four points along the translation modality spectrum

Translation Quality based on translation modality

Figure 1 displays modalities ranging from pure Machine Translation (MT) on the far left, to pure Human Translation (HT) on the right. In the intermediate space, modalities are arranged in order from 1) Unedited Machine Translation (UEMT) to 2) Post-Edited Machine Translation (PEMT) to 3) Human Translation (HT) with CAT tools to 4) HT only translation (without any support tools).

Although in some cases, the reader might assume a value range associated with these levels, the perspective offered by the spectrum is essentially focused on the modality chosen for target content production, bearing in mind that many different factors can also affect the quality of both MT and HT. Nevertheless, it is assumed that HT supported by adequate translation memories, terminology resources, and professional verification as defined in the standards (ASTM F2575, ISO 17100, and ISO 11669) poses less risk and promises higher final translation quality than other levels.

Theoretically, full PEMT also significantly reduces risk of error, with light post editing or sampling introducing additional risk of undetected error. UEMT, classified here as UVT, is then totally dependent on the quality of the MT (or AI/MT) that is used in any given case. Again, as with other views of the Translation Quality Spectrum, (high) Quality Translation tends to migrate to one side of the spectrum, with lower quality values balanced against the potentially reduced critical risk associated with less demanding use cases. Agreed-upon specifications reflect a tension between the intended purpose of target content balanced against translation cost and effort.

Conclusion

Translation Quality comprises a spectrum of values, ranging from low to high quality translation, but it also mirrors a range of required service levels, as well as a spectrum of client and end-user needs and expectations. MQM is designed to measure that Translation Quality in terms of the targeted spectrum and the factors that contribute to quality. This structured approach to quality measurement is the topic of following articles.